The birth and growth of financial technology developed mostly over the last ten years.

So as we look ahead, what does the next decade have in store? I believe we’re starting to see early signs: in the next ten years, fintech will become portable and ubiquitous as it moves to the background and centralizes into one place where our money is managed for us.

When I started working in fintech in 2012, I had trouble tracking competitive search terms because no one knew what our sector was called. The best-known companies in the space were Paypal and Mint.

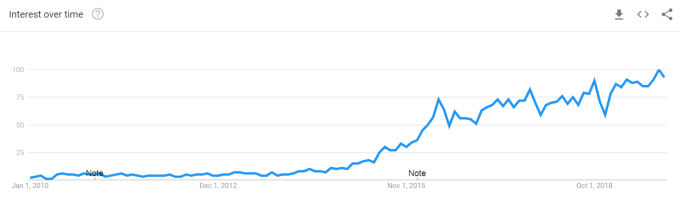

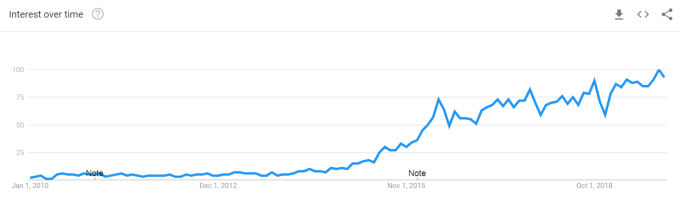

Google search volume for “fintech,” 2000 – present.

Fintech has since become a household name, a shift that came with with prodigious growth in investment: from $2 billion in 2010 to over $50 billion in venture capital in 2018 (and on-pace for $30 billion+ this year).

Predictions were made along the way with mixed results — banks will go out of business, banks will catch back up. Big tech will get into consumer finance. Narrow service providers will unbundle all of consumer finance. Banks and big fintechs will gobble up startups and consolidate the sector. Startups will each become their own banks. The fintech ‘bubble’ will burst.

https://ift.tt/35PCNan

Here’s what did happen: fintechs were (and still are) heavily verticalized, recreating the offline branches of financial services by bringing them online and introducing efficiencies. The next decade will look very different. Early signs are beginning to emerge from overlooked areas which suggest that financial services in the next decade will:

- Be portable and interoperable: Like mobile phones, customers will be able to easily transition between ‘carriers’.

- Become more ubiquitous and accessible: Basic financial products will become a commodity and bring unbanked participants ‘online’.

- Move to the background: The users of financial tools won’t have to develop 1:1 relationships with the providers of those tools.

- Centralize into a few places and steer on ‘autopilot’.

Prediction 1: The open data layer

Thesis: Data will be openly portable and will no longer be a competitive moat for fintechs.

Personal data has never had a moment in the spotlight quite like 2019. The Cambridge Analytica scandal and the data breach that compromised 145 million Equifax accounts sparked today’s public consciousness around the importance of data security. Last month, the House of Representatives’ Fintech Task Force met to evaluate financial data standards and the Senate introduced the Consumer Online Privacy Rights Act.

A tired cliché in tech today is that “data is the new oil.” Other things being equal, one would expect banks to exploit their data-rich advantage to build the best fintech. But while it’s necessary, data alone is not a sufficient competitive moat: great tech companies must interpret, understand and build customer-centric products that leverage their data.

Why will this change in the next decade? Because the walls around siloed customer data in financial services are coming down. This is opening the playing field for upstart fintech innovators to compete with billion-dollar banks, and it’s happening today.

Much of this is thanks to a relatively obscure piece of legislation in Europe, PSD2. Think of it as GDPR for payment data. The UK became the first to implement PSD2 policy under its Open Banking regime in 2018. The policy requires all large banks to make consumer data available to any fintech which the consumer permissions. So if I keep my savings with Bank A but want to leverage them to underwrite a mortgage with Fintech B, as a consumer I can now leverage my own data to access more products.

Consortia like FDATA are radically changing attitudes towards open banking and gaining global support. In the U.S., five federal financial regulators recently came together with a rare joint statement on the benefits of alternative data, for the most part only accessible through open banking technology.

The data layer, when it becomes open and ubiquitous, will erode the competitive advantage of data-rich financial institutions. This will democratize the bottom of the fintech stack and open the competition to whoever can build the best products on top of that openly accessible data… but building the best products is still no trivial feat, which is why Prediction 2 is so important:

Prediction 2: The open protocol layer

Thesis: Basic financial services will become simple open-source protocols, lowering the barrier for any company to offer financial products to its customers.

Picture any investment, wealth management, trading, merchant banking, or lending system. Just to get to market, these systems have to rigorously test their core functionality to avoid legal and regulatory risk. Then, they have to eliminate edge cases, build a compliance infrastructure, contract with third-party vendors to provide much of the underlying functionality (think: Fintech Toolkit) and make these systems all work together.

The end result is that every financial services provider builds similar systems, replicated over and over and siloed by company. Or even worse, they build on legacy core banking providers, with monolith systems in outdated languages (hello, COBOL). These services don’t interoperate, and each bank and fintech is forced to become its own expert at building financial protocols ancillary to its core service.

But three trends point to how that is changing today:

First, the infrastructure and service layer to build is being disaggregates, thanks to platforms like Stripe, Marqeta, Apex, and Plaid. These ‘finance as a service’ providers make it easy to build out basic financial functionality. Infrastructure is currently a hot investment category and will be as long as more companies get into financial services — and as long as infra market leaders can maintain price control and avoid commoditization.

Second, industry groups like FINOS are spearheading the push for open-source financial solutions. Consider a Github repository for all the basic functionality that underlies fintech tools. Developers could continuously improve the underlying code. Software could become standardized across the industry. Solutions offered by different service providers could become more inter-operable if they shared their underlying infrastructure.

And third, banks and investment managers, realizing the value in their own technology, are today starting to license that technology out. Examples are BlackRock’s Aladdin risk-management system or Goldman’s Alloy data modeling program. By giving away or selling these programs to clients, banks open up another revenue stream, make it easy for the financial services industry to work together (think of it as standardizing the language they all use), and open up a customer base that will provide helpful feedback, catch bugs, and request new useful product features.

As Andreessen Horowitz partner Angela Strange notes, “what that means is, there are several different infrastructure companies that will partner with banks and package up the licensing process and some regulatory work, and all the different payment-type networks that you need. So if you want to start a financial company, instead of spending two years and millions of dollars in forming tons of partnerships, you can get all of that as a service and get going.”

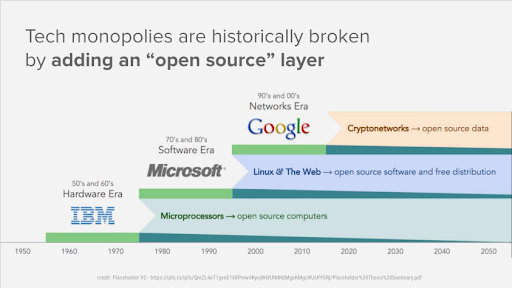

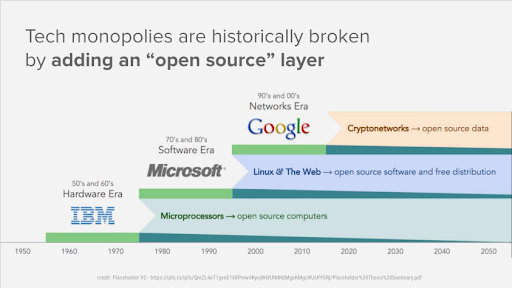

Fintech is developing in much the same way computers did: at first software and hardware came bundled, then hardware became below differentiated operating systems with ecosystem lock-in, then the internet broke open software with software-as-a-service. In that way, fintech in the next ten years will resemble the internet of the last twenty.

Infographic courtesy Placeholder VC

Prediction 3: Embedded fintech

Thesis: Fintech will become part of the basic functionality of non-finance products.

The concept of embedded fintech is that financial services, rather than being offered as a standalone product, will become part of the native user interface of other products, becoming embedded.

This prediction has gained supporters over the last few months, and it’s easy to see why. Bank partnerships and infrastructure software providers have inspired companies whose core competencies are not consumer finance to say “why not?” and dip their toes in fintech’s waters.

Apple debuted the Apple Card. Amazon offers its Amazon Pay and Amazon Cash products. Facebook unveiled its Libra project and, shortly afterward, launched Facebook Pay. As companies from Shopify to Target look to own their payment and purchase finance stacks, fintech will begin eating the world.

If these signals are indicative, financial services in the next decade will be a feature of the platforms with which consumers already have a direct relationship, rather than a product for which consumers need to develop a relationship with a new provider to gain access.

Matt Harris of Bain Capital Ventures summarizes in a recent set of essays (one, two) what it means for fintech to become embedded. His argument is that financial services will be the next layer of the ‘stack’ to build on top of internet, cloud, and mobile. We now have powerful tools that are constantly connected and immediately available to us through this stack, and embedded services like payments, transactions, and credit will allow us to unlock more value in them without managing our finances separately.

Fintech futurist Brett King puts it even more succinctly: technology companies and large consumer brands will become gatekeepers for financial products, which themselves will move to the background of the user experiences. Many of these companies have valuable data from providing sticky, high-affinity consumer products in other domains. That data can give them a proprietary advantage in cost-cutting or underwriting (eg: payment plans for new iPhones). The combination of first-order services (eg: making iPhones) with second-order embedded finance (eg: microloans) means that they can run either one as a loss-leader to subsidize the other, such as lowering the price of iPhones while increasing Apple’s take on transactions in the app store.

This is exciting for the consumers of fintech, who will no longer have to search for new ways to pay, invest, save, and spend. It will be a shift for any direct-to-consumer brands, who will be forced to compete on non-brand dimensions and could lose their customer relationships to aggregators.

Even so, legacy fintechs stand to gain from leveraging the audience of big tech companies to expand their reach and building off the contextual data of big tech platforms. Think of Uber rides hailed from within Google Maps: Uber made a calculated choice to list its supply on an aggregator in order to reach more customers right when they’re looking for directions.

Prediction 4: Bringing it all together

Thesis: Consumers will access financial services from one central hub.

In-line with the migration from front-end consumer brand to back-end financial plumbing, most financial services will centralize into hubs to be viewed all in one place.

For a consumer, the hub could be a smartphone. For a small business, within Quickbooks or Gmail or the cash register.

As companies like Facebook, Apple, and Amazon split their operating systems across platforms (think: Alexa + Amazon Prime + Amazon Credit Card), benefits will accrue to users who are fully committed to one ecosystem so that they can manage their finances through any platform — but these providers will make their platforms interoperable as well so that Alexa (e.g.) can still win over Android users.

As a fintech nerd, I love playing around with different financial products. But most people are not fintech nerds and prefer to interact with as few services as possible. Having to interface with multiple fintechs separately is ultimately value subtractive, not additive. And good products are designed around customer-centric intuition. In her piece, Google Maps for Money, Strange calls this ‘autonomous finance:’ your financial service products should know your own financial position better than you do so that they can make the best choices with your money and execute them in the background so you don’t have to.

And so now we see the rebundling of services. But are these the natural endpoints for fintech? As consumers become more accustomed to financial services as a natural feature of other products, they will probably interact more and more with services in the hubs from which they manage their lives. Tech companies have the natural advantage in designing the product UIs we love — do you enjoy spending more time on your bank’s website or your Instagram feed? Today, these hubs are smartphones and laptops. In the future, could they be others, like emails, cars, phones or search engines?

As the development of fintech mirrors the evolution of computers and the internet, becoming interoperable and embedded in everyday services, it will radically reshape where we manage our finances and how little we think about them anymore. One thing is certain: by the time I’m writing this article in 2029, fintech will look very little like it did today.

So which financial technology companies will be the ones to watch over the next decade? Building off these trends, we’ve picked five that will thrive in this changing environment.

from Android – TechCrunch https://ift.tt/35MdTbK

via

IFTTT

SpaceX’s latest launch took place on Monday, and it was a success in just about every regard – except in terms of one of its secondary missions, which was an attempt to catch the two fairing halves that together cover the payload as the rocket ascends to space. SpaceX has been trying to catch these with ships at sea equipped with large nets, and it’s caught one previously. It’ll keep trying, just like it did with rocket booster landings, and could save up to $6 million per launch once it gets the process right.

SpaceX’s latest launch took place on Monday, and it was a success in just about every regard – except in terms of one of its secondary missions, which was an attempt to catch the two fairing halves that together cover the payload as the rocket ascends to space. SpaceX has been trying to catch these with ships at sea equipped with large nets, and it’s caught one previously. It’ll keep trying, just like it did with rocket booster landings, and could save up to $6 million per launch once it gets the process right.

App Annie this week released its list of

App Annie this week released its list of

Apple

Apple  We hope you downloaded this fun app

We hope you downloaded this fun app