Last week, Apple announced a series of new features targeted at child safety on its devices. Though not live yet, the features will arrive later this year for users. Though the goals of these features are universally accepted to be good ones — the protection of minors and the limit of the spread of Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM), there have been some questions about the methods Apple is using.

I spoke to Erik Neuenschwander, Head of Privacy at Apple, about the new features launching for its devices. He shared detailed answers to many of the concerns that people have about the features and talked at length to some of the tactical and strategic issues that could come up once this system rolls out.

I also asked about the rollout of the features, which come closely intertwined but are really completely separate systems that have similar goals. To be specific, Apple is announcing three different things here, some of which are being confused with one another in coverage and in the minds of the public.

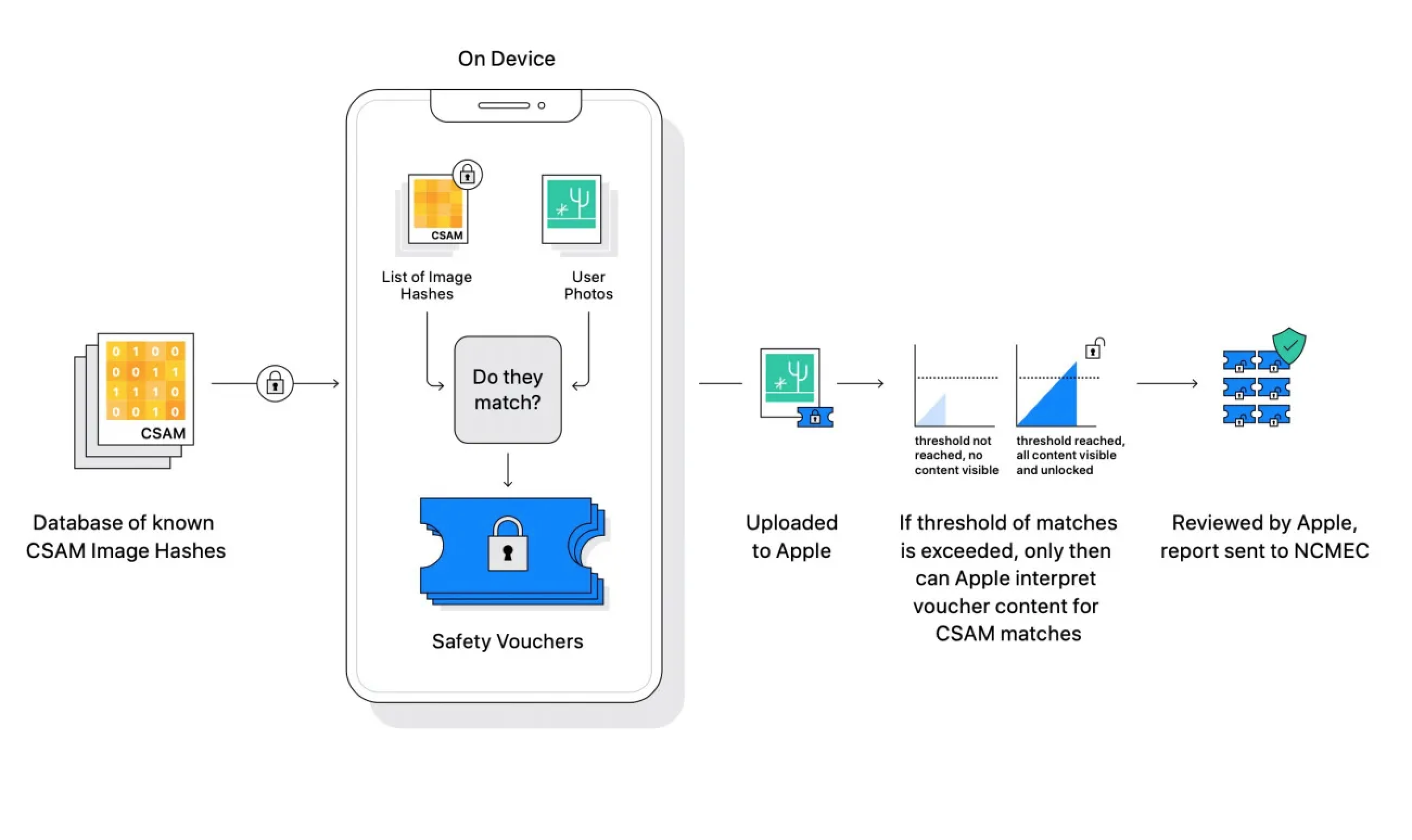

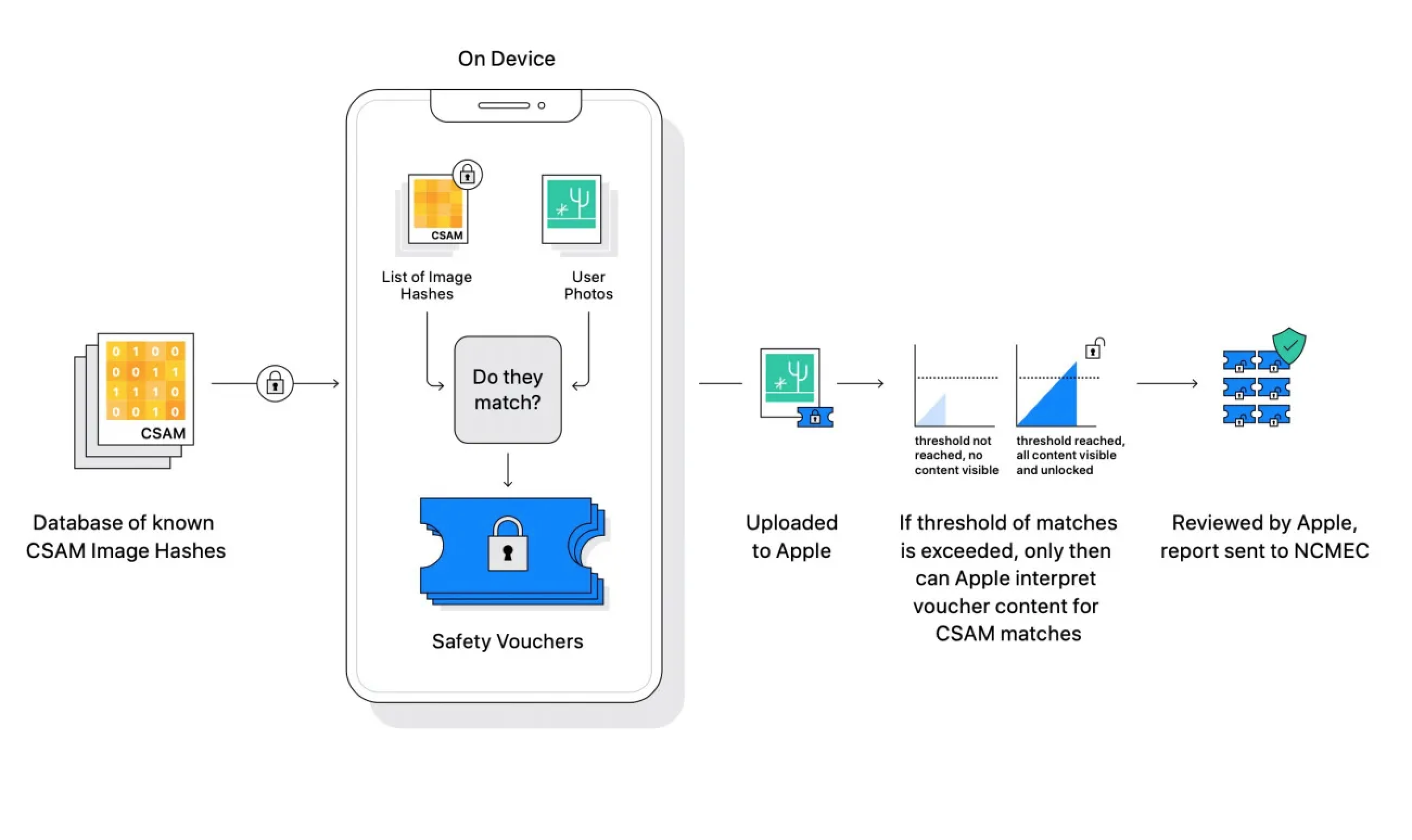

CSAM detection in iCloud Photos – A detection system called NeuralHash creates identifiers it can compare with IDs from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and other entities to detect known CSAM content in iCloud Photo libraries. Most cloud providers already scan user libraries for this information — Apple’s system is different in that it does the matching on device rather than in the cloud.

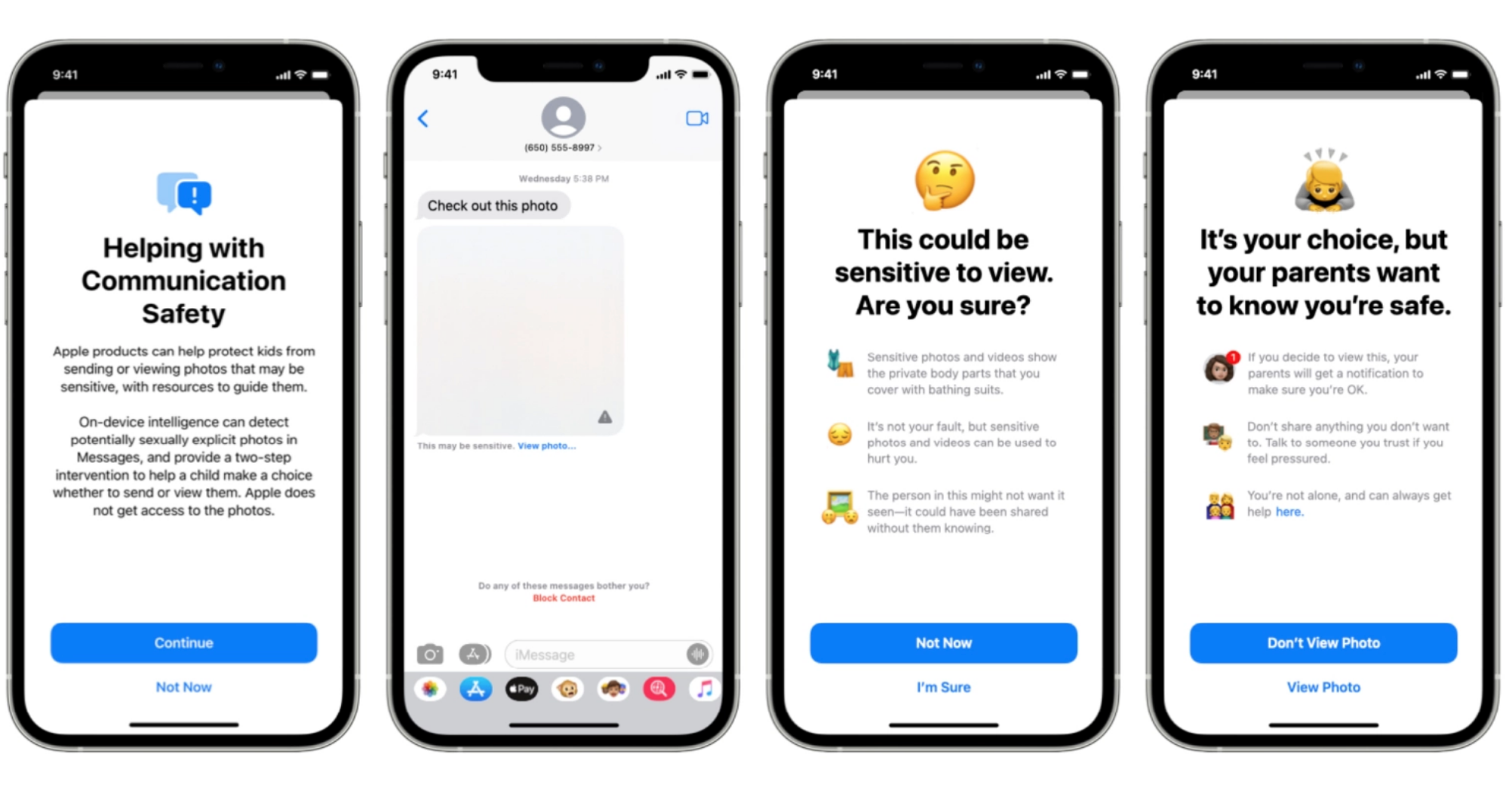

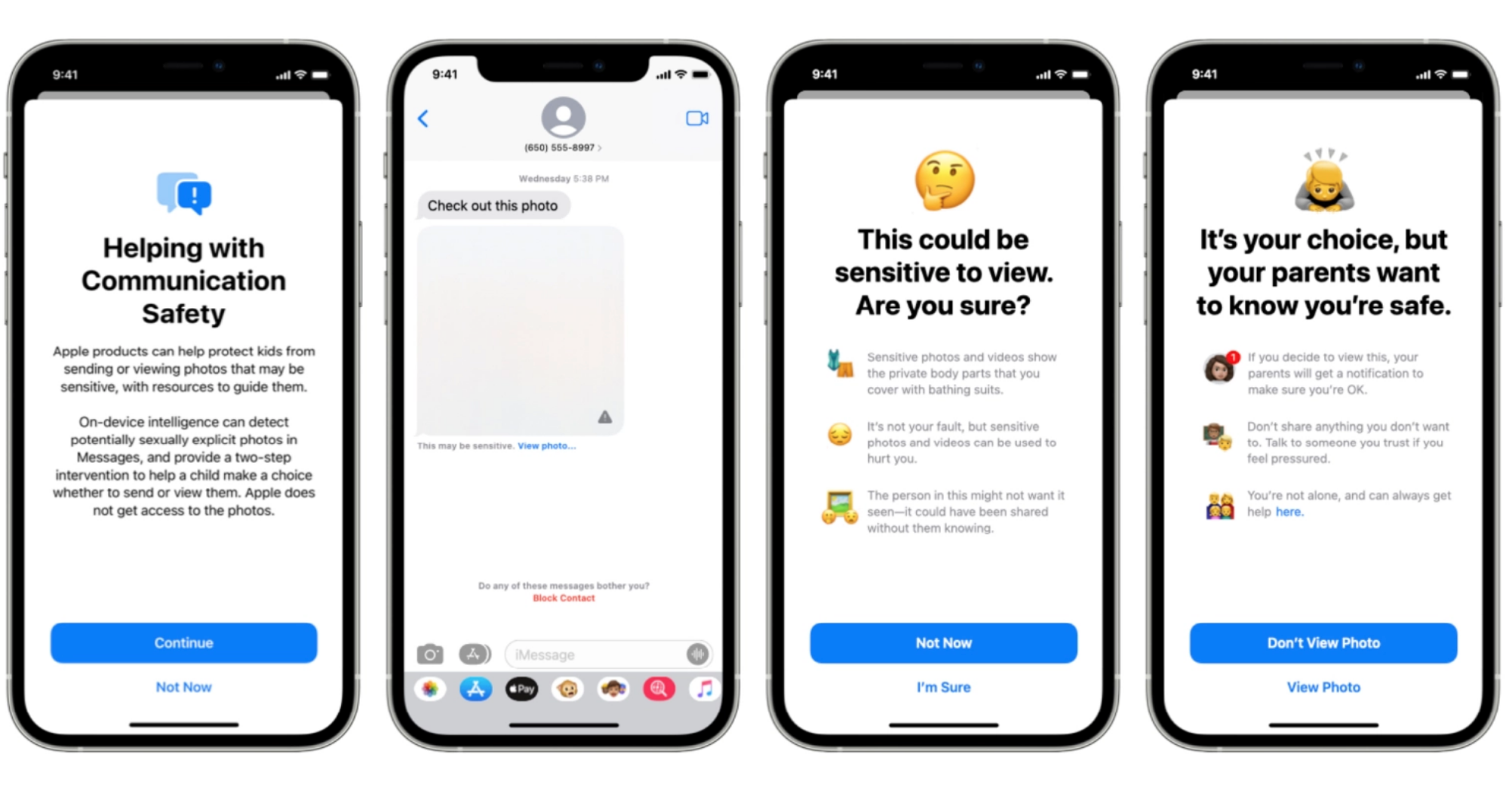

Communication Safety in Messages – A feature that a parent opts to turn on for a minor on their iCloud Family account. It will alert children when an image they are going to view has been detected to be explicit and it tells them that it will also alert the parent.

Interventions in Siri and search – A feature that will intervene when a user tries to search for CSAM-related terms through Siri and search and will inform the user of the intervention and offer resources.

For more on all of these features you can read our articles linked above or Apple’s new FAQ that it posted this weekend.

From personal experience, I know that there are people who don’t understand the difference between those first two systems, or assume that there will be some possibility that they may come under scrutiny for innocent pictures of their own children that may trigger some filter. It’s led to confusion in what is already a complex rollout of announcements. These two systems are completely separate, of course, with CSAM detection looking for precise matches with content that is already known to organizations to be abuse imagery. Communication Safety in Messages takes place entirely on the device and reports nothing externally — it’s just there to flag to a child that they are or could be about to be viewing explicit images. This feature is opt-in by the parent and transparent to both parent and child that it is enabled.

Apple’s Communication Safety in Messages feature. Image Credits: Apple

There have also been questions about the on-device hashing of photos to create identifiers that can be compared with the database. Though NeuralHash is a technology that can be used for other kinds of features like faster search in photos, it’s not currently used for anything else on iPhone aside from CSAM detection. When iCloud Photos is disabled, the feature stops working completely. This offers an opt-out for people but at an admittedly steep cost given the convenience and integration of iCloud Photos with Apple’s operating systems.

Though this interview won’t answer every possible question related to these new features, this is the most extensive on-the-record discussion by Apple’s senior privacy member. It seems clear from Apple’s willingness to provide access and its ongoing FAQ’s and press briefings (there have been at least 3 so far and likely many more to come) that it feels that it has a good solution here.

Despite the concerns and resistance, it seems as if it is willing to take as much time as is necessary to convince everyone of that.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

TC: Most other cloud providers have been scanning for CSAM for some time now. Apple has not. Obviously there are no current regulations that say that you must seek it out on your servers, but there is some roiling regulation in the EU and other countries. Is that the impetus for this? Basically, why now?

Erik Neuenschwander: Why now comes down to the fact that we’ve now got the technology that can balance strong child safety and user privacy. This is an area we’ve been looking at for some time, including current state of the art techniques which mostly involves scanning through entire contents of users libraries on cloud services that — as you point out — isn’t something that we’ve ever done; to look through user’s iCloud Photos. This system doesn’t change that either, it neither looks through data on the device, nor does it look through all photos in iCloud Photos. Instead what it does is gives us a new ability to identify accounts which are starting collections of known CSAM.

So the development of this new CSAM detection technology is the watershed that makes now the time to launch this. And Apple feels that it can do it in a way that it feels comfortable with and that is ‘good’ for your users?

That’s exactly right. We have two co-equal goals here. One is to improve child safety on the platform and the second is to preserve user privacy, And what we’ve been able to do across all three of the features, is bring together technologies that let us deliver on both of those goals.

Announcing the Communications safety in Messages features and the CSAM detection in iCloud Photos system at the same time seems to have created confusion about their capabilities and goals. Was it a good idea to announce them concurrently? And why were they announced concurrently, if they are separate systems?

Well, while they are [two] systems they are also of a piece along with our increased interventions that will be coming in Siri and search. As important as it is to identify collections of known CSAM where they are stored in Apple’s iCloud Photos service, It’s also important to try to get upstream of that already horrible situation. So CSAM detection means that there’s already known CSAM that has been through the reporting process, and is being shared widely re-victimizing children on top of the abuse that had to happen to create that material in the first place. for the creator of that material in the first place. And so to do that, I think is an important step, but it is also important to do things to intervene earlier on when people are beginning to enter into this problematic and harmful area, or if there are already abusers trying to groom or to bring children into situations where abuse can take place, and Communication Safety in Messages and our interventions in Siri and search actually strike at those parts of the process. So we’re really trying to disrupt the cycles that lead to CSAM that then ultimately might get detected by our system.

The process of Apple’s CSAM detection in iCloud Photos system. Image Credits: Apple

Governments and agencies worldwide are constantly pressuring all large organizations that have any sort of end-to-end or even partial encryption enabled for their users. They often lean on CSAM and possible terrorism activities as rationale to argue for backdoors or encryption defeat measures. Is launching the feature and this capability with on-device hash matching an effort to stave off those requests and say, look, we can provide you with the information that you require to track down and prevent CSAM activity — but without compromising a user’s privacy?

So, first, you talked about the device matching so I just want to underscore that the system as designed doesn’t reveal — in the way that people might traditionally think of a match — the result of the match to the device or, even if you consider the vouchers that the device creates, to Apple. Apple is unable to process individual vouchers; instead, all the properties of our system mean that it’s only once an account has accumulated a collection of vouchers associated with illegal, known CSAM images that we are able to learn anything about the user’s account.

Now, why to do it is because, as you said, this is something that will provide that detection capability while preserving user privacy. We’re motivated by the need to do more for child safety across the digital ecosystem, and all three of our features, I think, take very positive steps in that direction. At the same time we’re going to leave privacy undisturbed for everyone not engaged in the illegal activity.

Does this, creating a framework to allow scanning and matching of on-device content, create a framework for outside law enforcement to counter with, ‘we can give you a list, we don’t want to look at all of the user’s data but we can give you a list of content that we’d like you to match’. And if you can match it with this content you can match it with other content we want to search for. How does it not undermine Apple’s current position of ‘hey, we can’t decrypt the user’s device, it’s encrypted, we don’t hold the key?’

It doesn’t change that one iota. The device is still encrypted, we still don’t hold the key, and the system is designed to function on on-device data. What we’ve designed has a device side component — and it has the device side component by the way, for privacy improvements. The alternative of just processing by going through and trying to evaluate users data on a server is actually more amenable to changes [without user knowledge], and less protective of user privacy.

Our system involves both an on-device component where the voucher is created, but nothing is learned, and a server-side component, which is where that voucher is sent along with data coming to Apple service and processed across the account to learn if there are collections of illegal CSAM. That means that it is a service feature. I understand that it’s a complex attribute that a feature of the service has a portion where the voucher is generated on the device, but again, nothing’s learned about the content on the device. The voucher generation is actually exactly what enables us not to have to begin processing all users’ content on our servers which we’ve never done for iCloud Photos. It’s those sorts of systems that I think are more troubling when it comes to the privacy properties — or how they could be changed without any user insight or knowledge to do things other than what they were designed to do.

One of the bigger queries about this system is that Apple has said that it will just refuse action if it is asked by a government or other agency to compromise by adding things that are not CSAM to the database to check for them on-device. There are some examples where Apple has had to comply with local law at the highest levels if it wants to operate there, China being an example. So how do we trust that Apple is going to hew to this rejection of interference If pressured or asked by a government to compromise the system?

Well first, that is launching only for US, iCloud accounts, and so the hypotheticals seem to bring up generic countries or other countries that aren’t the US when they speak in that way, and the therefore it seems to be the case that people agree US law doesn’t offer these kinds of capabilities to our government.

But even in the case where we’re talking about some attempt to change the system, it has a number of protections built in that make it not very useful for trying to identify individuals holding specifically objectionable images. The hash list is built into the operating system, we have one global operating system and don’t have the ability to target updates to individual users and so hash lists will be shared by all users when the system is enabled. And secondly, the system requires the threshold of images to be exceeded so trying to seek out even a single image from a person’s device or set of people’s devices won’t work because the system simply does not provide any knowledge to Apple for single photos stored in our service. And then, thirdly, the system has built into it a stage of manual review where, if an account is flagged with a collection of illegal CSAM material, an Apple team will review that to make sure that it is a correct match of illegal CSAM material prior to making any referral to any external entity. And so the hypothetical requires jumping over a lot of hoops, including having Apple change its internal process to refer material that is not illegal, like known CSAM and that we don’t believe that there’s a basis on which people will be able to make that request in the US. And the last point that I would just add is that it does still preserve user choice, if a user does not like this kind of functionality, they can choose not to use iCloud Photos and if iCloud Photos is not enabled no part of the system is functional.

So if iCloud Photos is disabled, the system does not work, which is the public language in the FAQ. I just wanted to ask specifically, when you disable iCloud Photos, does this system continue to create hashes of your photos on device, or is it completely inactive at that point?

If users are not using iCloud Photos, NeuralHash will not run and will not generate any vouchers. CSAM detection is a neural hash being compared against a database of the known CSAM hashes that are part of the operating system image. None of that piece, nor any of the additional parts including the creation of the safety vouchers or the uploading of vouchers to iCloud Photos is functioning if you’re not using iCloud Photos.

In recent years, Apple has often leaned into the fact that on-device processing preserves user privacy. And in nearly every previous case and I can think of that’s true. Scanning photos to identify their content and allow me to search them, for instance. I’d rather that be done locally and never sent to a server. However, in this case, it seems like there may actually be a sort of anti-effect in that you’re scanning locally, but for external use cases, rather than scanning for personal use — creating a ‘less trust’ scenario in the minds of some users. Add to this that every other cloud provider scans it on their servers and the question becomes why should this implementation being different from most others engender more trust in the user rather than less?

I think we’re raising the bar, compared to the industry standard way to do this. Any sort of server side algorithm that’s processing all users photos is putting that data at more risk of disclosure and is, by definition, less transparent in terms of what it’s doing on top of the user’s library. So, by building this into our operating system, we gain the same properties that the integrity of the operating system provides already across so many other features, the one global operating system that’s the same for all users who download it and install it, and so it in one property is much more challenging, even how it would be targeted to an individual user. On the server side that’s actually quite easy — trivial. To be able to have some of the properties and building it into the device and ensuring it’s the same for all users with the features enable give a strong privacy property.

Secondly, you point out how use of on device technology is privacy preserving, and in this case, that’s a representation that I would make to you, again. That it’s really the alternative to where users’ libraries have to be processed on a server that is less private.

The things that we can say with this system is that it leaves privacy completely undisturbed for every other user who’s not into this illegal behavior, Apple gain no additional knowledge about any users cloud library. No user’s iCloud Library has to be processed as a result of this feature. Instead what we’re able to do is to create these cryptographic safety vouchers. They have mathematical properties that say, Apple will only be able to decrypt the contents or learn anything about the images and users specifically that collect photos that match illegal, known CSAM hashes, and that’s just not something anyone can say about a cloud processing scanning service, where every single image has to be processed in a clear decrypted form and run by routine to determine who knows what? At that point it’s very easy to determine anything you want [about a user’s images] versus our system only what is determined to be those images that match a set of known CSAM hashes that came directly from NCMEC and and other child safety organizations.

Can this CSAM detection feature stay holistic when the device is physically compromised? Sometimes cryptography gets bypassed locally, somebody has the device in hand — are there any additional layers there?

I think it’s important to underscore how very challenging and expensive and rare this is. It’s not a practical concern for most users though it’s one we take very seriously, because the protection of data on the device is paramount for us. And so if we engage in the hypothetical where we say that there has been an attack on someone’s device: that is such a powerful attack that there are many things that that attacker could attempt to do to that user. There’s a lot of a user’s data that they could potentially get access to. And the idea that the most valuable thing that an attacker — who’s undergone such an extremely difficult action as breaching someone’s device — was that they would want to trigger a manual review of an account doesn’t make much sense.

Because, let’s remember, even if the threshold is met, and we have some vouchers that are decrypted by Apple. The next stage is a manual review to determine if that account should be referred to NCMEC or not, and that is something that we want to only occur in cases where it’s a legitimate high value report. We’ve designed the system in that way, but if we consider the attack scenario you brought up, I think that’s not a very compelling outcome to an attacker.

Why is there a threshold of images for reporting, isn’t one piece of CSAM content too many?

We want to ensure that the reports that we make to NCMEC are high value and actionable, and one of the notions of all systems is that there’s some uncertainty built in to whether or not that image matched, And so the threshold allows us to reach that point where we expect a false reporting rate for review of one in 1 trillion accounts per year. So, working against the idea that we do not have any interest in looking through users’ photo libraries outside those that are holding collections of known CSAM the threshold allows us to have high confidence that those accounts that we review are ones that when we refer to NCMEC, law enforcement will be able to take up and effectively investigate, prosecute and convict.

from iPhone – TechCrunch https://ift.tt/2Vz8Coh